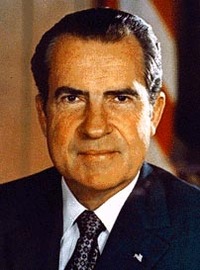

I have been remiss in not describing,

in detail, the political myth and values that now dominate American

politics.

I call it the Nixon Thesis of Conflict,

because most of it originated with Richard M. Nixon. Its assumptions

include the ideas that political adversaries are enemies, that

politics is a form of war, that attack is always better than defense,

and that the system is always under threat from outside.

As with most Political Theses in

American history, the Nixon Thesis is made from bits of the old

AntiThesis, combined with the character of the leader and the nature

of the crisis he rode in on. The AntiThesis in this case was

McCarthyism, the character of the leader is Nixon’s personal myth of

the Great Man, and the crisis was what we called the 1960s.

It’s the crisis that ties all this

together, and the political crisis of the 1960s was misunderstood for

a long, long time. Seeing the 60s from the point of view of the

anti-war movement is a lot like seeing the Civil War from the point

of view of the South. Culture makes it the popular view. But that’s

not how it went down.

Middle class Americans felt threatened

by the changes of the 1960s. By constantly conjuring up the threat

(whether or not it exists) leaders under the Nixon Thesis can get the

political knees to jerk, and impose their will. It’s the equivalent

of Republicans in the late 19th century “waving the

bloody shirt,” calling all Democrats potential traitors because

they either fought against the Union or urged peace with the

Confederacy.

All this mixed in the character of

Nixon himself. His early achievement was to make McCarthyism

legitimate. He used it strategically, targeting only specific

individuals who stood in the way of his own drive for power.

Eisenhower brought Nixon into national politics because he believed

he could give him the energy of McCarthy’s troops without the

craziness, the assumptions of the movement yoked to the necessities

of the Cold War.

But the craziness was always there,

hidden behind a mask of affability. In was unleashed in the form of

Nixon’s Vice President, Spiro Agnew, and Agnew’s speechwriter,

William Safire. Groups to be cowed were chosen carefully –

students, the media, intellectuals. The purpose was to place these

groups on the other side of the political divide but to show

potential members of those groups a way to salvation, subordination

to the will of the Movement.

The Movement in this case was the

Goldwater Movement. Nixon himself always had an arms-length

relationship to Movement Conservatives. He had come from a different

time and was not one of “them.” But he could bring them to power

– he could “win” — and the Movement would inherit that power.

Power was Nixon’s aim, the power to

change history by manipulating ideology. He fed the Movement

rhetoric, but in many ways leaned against the previous regime, as an

AntiThesis politician will. The results were a host of liberal

initiatives – the EPA, OSHA, the CPSC, judges who seemed

conservative but accepted liberalism’s premises. Nixon left the

Movement with a generation’s worth of work to do, which I think was

his intention. .

Watergate and Vietnam may be the most

misunderstood elements of the Nixon Thesis. They were personal

failures for the man, but for the Movement they were, and remain,

causes to be overcome. To adherents of the Nixon Thesis these were

merely failures of nerve. This is expressed explicitly by Vice

President Cheney, in the case of Watergate, and by President George

W. Bush himself, in the case of Vietnam. Destroy the evidence, refuse

to retreat, and any aim can be achieved.

The Nixon Thesis worked. It brought the

Movement to power. In the form of Reaganism, that movement triumphed

in its ultimate aim, which was to win the Cold War through

confrontation. But once that war was won, the assumptions of the

Thesis continued to work, always seeking new enemies, and building

those enemies into dire threats.

George W. Bush, whose Administration

represents the Excess of this Thesis, is not an idiot. He is a

believer in what he was taught, an acolyte of the Nixon Thesis and

the conservative Movement it brought to power. In this he is no

different from Lyndon Johnson, who believed in the FDR Thesis, or

Herbert Hoover, who believed the Teddy Roosevelt Thesis, or even of

James Buchanan, an adherent of the Andrew Jackson Thesis.

Any political movement, born in crisis,

becomes obsolete when a new crisis emerges it is not designed to

handle. The Jackson Thesis of balancing regions could not stop the

Civil War. The Teddy Roosevelt Thesis of measured change could not

deal with the Great Depression. The FDR Thesis of unity cracked under

the strains of the 1960s. And so the Nixon Thesis has expired in Iraq

and Katrina.

The Nixon Thesis, like all these theses

of the past, collapsed because history moved on, creating new crises

it was not built to handle.

That’s where we are today, seeking a

new Thesis that can deal with the environmental, and energy crises

that threaten, not just the suburbs, not just the United States, but

the whole world.

You make many good points in your article. I would like to supplement them with some information:

I am a 2 tour Vietnam Veteran who recently retired after 36 years of working in the Defense Industrial Complex on many of the weapons systems being used by our forces as we speak.

If you are interested in a view of the inside of the Pentagon procurement process from Vietnam to Iraq please check the posting at my blog entitled, “Odyssey of Armements”

The Pentagon is a giant, incredibly complex establishment,budgeted in excess of $500B per year. The Rumsfelds, the Adminisitrations and the Congressmen come and go but the real machinery of policy and procurement keeps grinding away, presenting the politicos who arrive with detail and alternatives slanted to perpetuate itself.

How can any newcomer, be he a President, a Congressman or even the Sec. Def. to be – Mr. Gates- understand such complexity, particulary if heretofore he has not had the clearance to get the full details?

Answer- he can’t. Therefor he accepts the alternatives provided by the career establishment that never goes away and he hopes he makes the right choices. Or he is influenced by a lobbyist or two representing companies in his district or special interest groups.

From a practical standpoint, policy and war decisions are made far below the levels of the talking heads who take the heat or the credit for the results.

This situation is unfortunate but it is ablsolute fact. Take it from one who has been to war and worked in the establishment.

This giant policy making and war machine will eventually come apart and have to be put back together to operate smaller, leaner and on less fuel. But that won’t happen unitil it hits a brick wall at high speed.

We will then have to run a Volkswagon instead of a Caddy and get along somehow. We better start practicing now and get off our high horse. Our golden aura in the world is beginning to dull from arrogance.

You make many good points in your article. I would like to supplement them with some information:

I am a 2 tour Vietnam Veteran who recently retired after 36 years of working in the Defense Industrial Complex on many of the weapons systems being used by our forces as we speak.

If you are interested in a view of the inside of the Pentagon procurement process from Vietnam to Iraq please check the posting at my blog entitled, “Odyssey of Armements”

The Pentagon is a giant, incredibly complex establishment,budgeted in excess of $500B per year. The Rumsfelds, the Adminisitrations and the Congressmen come and go but the real machinery of policy and procurement keeps grinding away, presenting the politicos who arrive with detail and alternatives slanted to perpetuate itself.

How can any newcomer, be he a President, a Congressman or even the Sec. Def. to be – Mr. Gates- understand such complexity, particulary if heretofore he has not had the clearance to get the full details?

Answer- he can’t. Therefor he accepts the alternatives provided by the career establishment that never goes away and he hopes he makes the right choices. Or he is influenced by a lobbyist or two representing companies in his district or special interest groups.

From a practical standpoint, policy and war decisions are made far below the levels of the talking heads who take the heat or the credit for the results.

This situation is unfortunate but it is ablsolute fact. Take it from one who has been to war and worked in the establishment.

This giant policy making and war machine will eventually come apart and have to be put back together to operate smaller, leaner and on less fuel. But that won’t happen unitil it hits a brick wall at high speed.

We will then have to run a Volkswagon instead of a Caddy and get along somehow. We better start practicing now and get off our high horse. Our golden aura in the world is beginning to dull from arrogance.

Blogs are good for every one where we get lots of information for any topics nice job keep it up !!!

Blogs are good for every one where we get lots of information for any topics nice job keep it up !!!

Excellent Blog every one can get lots of information for any topics from this blog nice work keep it up.

thanks

Excellent Blog every one can get lots of information for any topics from this blog nice work keep it up.

thanks

“Any political movement, born in crisis, becomes obsolete when a new crisis emerges it is not designed to handle.”

Explains a lot, especially when you add that no one wants to be removed from power.

I find your meme of development of successive thesi very hopeful.

Thanks, Dana!

“Any political movement, born in crisis, becomes obsolete when a new crisis emerges it is not designed to handle.”

Explains a lot, especially when you add that no one wants to be removed from power.

I find your meme of development of successive thesi very hopeful.

Thanks, Dana!

Missing MR.BUSH….

🙁

Missing MR.BUSH….

🙁

I agree with most of the points you make within this content.

I agree with most of the points you make within this content.

I agree with most of the points you make within this content.

I agree with most of the points you make within this content.