Chris Bruntlett has worn many hats during his career. An architect. A writer. An advocate.

Chris Bruntlett has worn many hats during his career. An architect. A writer. An advocate.

The one that fits best may be that of a diplomat. His Dutch Cycling Embassy is in the business of advising on urban mobility, based on a model that works, that of the Netherlands. To that end, he has evolved a diplomatic mien, and a willingness to tolerate fools (like me) that can get him into the rooms where it happens, around the world.

Near the end of my two month long visit to the Netherlands I sat down with Chris to talk about what’s happening. He had just returned from China, which has been forced to deal for decades with questions that America is only now discovering exist. Like how people get around when population density gets too intense for cars.

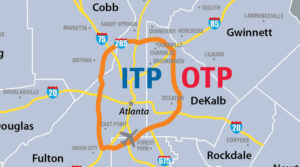

“Even in sprawling car dependent cities, there is some low hanging fruit that you can focus on,” he said. “In cities like Atlanta and Austin and LA, half of all the car journeys are three miles or less. We now have traffic modeling software that identify where those journeys are taking place.” Austin, Texas, for instance, created “heat maps” of those journeys, then built a cycling network to capture just 15% of them.” This cuts traffic jams without widening roads.

What About Atlanta?

The east side of town, where I live, works that way already. On most roads it’s impractical to go faster than 20. Only on a few main roads do cars regularly move as fast as 30, usually at night or for short stretches. Designing the road network so cars are directed onto the main roads, and off the shared roads, is the first step toward making bicycling safe.

But in Atlanta even this is going to be a slog. Drivers here assume they own the road, the whole road. They come in from suburbs where this is the case. So, some drivers park on bike paths. Some drive on them. Where bollards or other obstacles (like planters) exist, they run over them. Getting police to take this issue seriously is hard. Police can be the worst offenders.

Parking is where the rubber hits the road for both sides of the debate. Residents who want slower roads park on them, turning three lanes into one, which the bicycles and giant pick-up trucks then fight over. Guess who wins? Changing the subject is imperative, but what if no one will?

Back to the Netherlands

When I talk about this, Chris brings the subject back to China, where paths are dominated by electric mopeds. “Pedal assist does not exist in China,” he says. Mopeds are “dominating the infrastructure, creating all kinds of pressures on the public space, and the charging infrastructure.”

Going from gas to electric power doesn’t solve the problem. You need to slow traffic down to bicycle speeds to make the roads safe. All the infrastructure that makes the Netherlands attractive is being stretched to its limits in Beijing, where you can rent a bike for pennies.

The good news is that China has done a course correction, from encouraging cars for the economy to encouraging bikes for their mobility. One more lane will never do it.

Here’s the bottom line. We need to change how our roads are designed, and how they’re used, if we’re ever to get around cities safely. Chris has learned we can’t force it. It can only happen one city at a time, and one project at a time, through negotiation, through careful study, and using diplomacy.

I wish this was all easier.