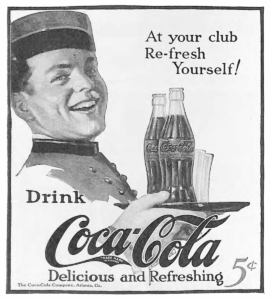

Rather than wade in on one side or the other, newly installed President Robert Woodruff changed the subject. What must we do, he asked, to make every Coca-Cola taste the same as every other Coca-Cola, no matter where you buy it? (That’s one of the ads which emerged from this understanding.)

The answer was water treatment. It made Coke a safe, healthy drink everywhere. Coke’s success, in turn, built Atlanta.

I was told this story in 1982, as a young reporter for the Atlanta Business Chronicle, by George Woodruff, Mr. Robert’s brother. And it’s relevant today.

They’re fighting over housing. They’re arguing over parking.

A better question is how we safely make the short, 3-5 miles trips that represent over half our urban traffic today.

There’s an answer to that question. The traffic treatment answer, like the water treatment answer of 100 years ago, is right in front of us.

The E-Transport Solution

The answer is electric. It starts with e-bikes, which can crush Atlanta’s hills and make everything else possible. My Edison e-bike can travel 5 miles in a half-hour, and I’m 70. Atlanta now has cargo bikes that can take kids to school and bring groceries home. Fat Dutch kids have fat-tire e-bikes that zip along at 28 mph. Many who can’t cycle, who have trouble even walking, zip around in mobility scooters that can go 15 mph on a proper surface.

It’s our insistence on living in the 20th century, in rolling living rooms which sit empty 90% of the time, that is clogging city streets.

The process can start with residential speed limits of 20 mph, which is compatible with e-transport. Neighborhood groups and NPUs can lead the way here. On residential streets where you can’t go faster already, and on commercial strips crowded with shops and bars, a limit of 20 is practical and can be enforced.

Cars are just one way to get around. They should be guests on our roads. People should be the priority.

Summing Up

In the Netherlands, over half of all people commute by car. There are still freeways and car-friendly roads with limits of 40 and 60. There are still traffic jams.

It’s for those short trips within the city, to the store or the school, to a restaurant or a soccer practice, or a nearby job, where people need the safe alternatives that electricity can give them.

It must be safe to get around. For roads that go to places where speed is the only priority, a rolling living room is fine. There just isn’t enough room in a dense city for all those rolling living rooms to live.

For roads that take us within places, safety must be the priority. You’ll get there faster anyway if you’re not spending half the trip looking for a parking place.